Case Study developed by Salat, Serge. 2022. Urban Morphology and Complex Systems Institute 2022. © UMCSII.

design charrettes in fukushima, japan

Community involvement is an essential part of the common approach of Green and Thriving Neighbourhoods. It can make the projects fit community challenges and aspirations, foster people-centred transformation, improve design proposals, speed the process, and foster a sense of ownership. Involving residents and stakeholders in the development of a master plan improves its feasibility significantly. Design charrettes are among the best options and are a holistic process in which sustainable design emerges from the interaction of social, ecological, and economic variables in a collaborative and creative environment. Charrettes are also well adapted to post-disaster participatory reconstruction. This will be shown on a design charrette in Minamisoma City, Japan, after the Fukushima accident.

Key partners and actors

After the Fukushima disaster, both the central government of Japan and local government of Minamisoma set up a series of guidelines for reconstruction. The Minamisoma government issued the Minamisoma City Revitalization Plan in November 2011 and founded two administration departments leading the reconstruction, which are the Minamisoma City Revitalization Citizen’s Committee and the Minamisoma City Revitalization Expert Committee. The former organization is made up of city officials, community organization representatives and citizens, while the latter comprises academic experts from various fields.

The Minamisoma charrette was sponsored by a local NGO – the Association of Eco Energy of Minamisoma (AEM). Fourteen experts in land use, landscape design, community resilience, farming, geographic information science and environmental management participated in the entire charrette process. The experts were from Keio University in Japan, Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, and VHL University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. All the land-use and landscape-design experts were from non-Japanese-speaking countries. Residents were recruited by the local NGO and participated voluntarily. The preliminary preparations involved a site visit, interview, disaster explanation session and focus group session. The site visits were selected by AEM and included major communities that had been affected by the tsunami and nuclear explosion, large agricultural farms, enterprises that processed agricultural products, the historical culture sites, and the implementation site of the solar energy project. During the visits, the participants performed unstructured interviews with 10 randomly selected residents.

1. How to organise a design charrette

Design charrettes are a holistic process where sustainable design emerges from the interaction of social, ecological and economic variables through a collaborative and creative activity. A typical visioning charrette lasts a full week. Issues of sustainable community design are complex and require time to work out. At the beginning of the charrette the talk time builds trust and understanding within the team. When interpersonal empathy is established, ideas can start to evolve in diagrammatic form. Such diagrams are emerging syntheses in form. The final phase is the drawing phase and starts when all members of the team are comfortable with the direction set in the diagrams.

In the collaborative, hands-on sessions, participants help planners root out potential problems, identify and debate solutions, and create a buildable plan. The charrette compresses the planning process into a matter of days and brings all the stakeholders – and all the issues – into one room.

The process of making a good charrette is summarised as follows:

Design with everyone. A good charrette is a collaborative problem-solving design exercise to which the community should participate. Design is more a way of thinking than a set of technical skills. Most problem-solving modes proceed linearly and depend on the orderly execution of certain technical tasks. However, sustainable design requires a more qualitative approach depending on intuition and judgement to select from alternatives. Most community individuals have enough intuition and judgement to add value to well-designed charrette effort.

Start with a blank sheet. The blank sheet expresses both possibility and challenge. It is important as a symbol of community empowerment. If a sheet has too many, or even any, decisions already depicted, if for example basic land uses have already been assigned, the opportunities to explore mixed-use and sustainable strategies are limited. If both land use and transportation decisions have already been made, the charrette has lost its meaning.

Build from the policy base. Charrettes must be firmly grounded in existing policy. A direct link should be made between policy at the national, regional and local level each element of the design brief. The blank sheet should be completed with an explicit set of programme requirements tied to policy. The charrette task is to make programme requirements real. It links them to the context and site via a collaborative process of synthesis and synergy.

Provide just enough information. The key is to provide just enough data and no more. Too much information generates decision paralysis. Too little knowledge produces bad proposals.

Talk, create schematics, draw. Participants should initially talk about their ideas, gradually move to schematics, and finally draw out their vision. This process should not be rushed because it takes time to unpack the issues of community sustainability, to give everybody the opportunity to express their opinions, and to transform stakeholders into a cohesive team.

The charrette format usually brings quick results and can boost creativity. Furthermore, participants can observe the project from an integrated point of view because charrettes bring together all relevant disciplines to create a plan that balances transportation, land use, economic considerations, and environmental issues.

2. How to apply a design charrette process to post-disaster recovery

Post-disaster recovery is a social process that involves policy decisions, institutional capacities and sometimes conflicts between interest groups. In this process, the participation of local stakeholders should play an important role. The charrette is a useful method for building resilience and collaboration in the post-disaster context.

A 9.0-magnitude earthquake hit the east coast of Japan in March 2011. The quake – one of the most devastating in human history – triggered a tsunami, which then caused the hydrogen explosion in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP).

A large quantity of radionuclides leaked from the plant and polluted the natural and artificial environment, not only seriously affecting the lives of residents nearby, but also posing a hazard to the rest of Japan. The accident was thus rated Level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale, the most severe one since the Chernobyl accident.

Minamisoma City faces the Pacific Ocean in the east and has a total area of 398.50 km2. As a coastal town near the FDNPP, Minamisoma is one of the worst-hit regions in Fukushima: 636 people died directly from the disaster and nearly 3000 houses were demolished. After the nuclear explosion, the number of evacuees from Minamisoma accounted for 42% of all the evacuees in Fukushima. The Fukushima disaster also devastated the pre-existing industries in Minamisoma. Agriculture products, which used to have a good reputation, find no market. Manufacturing and other sectors are barely running below the full capacity due to the acute shortage of labour force.

The map of the study area: Minamisoma City. Source: Zhang, H., Mao, Z., & Zhang, W. (2015).

The Minamisoma charrette lasted for 10 days, from 7 to 17 September 2014. The event was sponsored by a local NGO – the Association of Eco Energy of Minamisoma (AEM). Fourteen experts in land use, landscape design, community resilience, farming, geographic information science and environmental management participated in the entire charrette process with the residents[1].

The charrette process included three stages:

preliminary preparation

design and planning

presentation and discussion

The primary objective of the preliminary preparation was to identify problems and unmet recovery needs from the residents by gathering materials and information that were relevant to the reconstruction process. This stage provided the foundation for the next stage. In the design and planning stage, the material collected from the previous stage was analysed, and design ideas were generated. The participants then organised the ideas and produced a preliminary plan. The presentation and discussion stage involved presenting a plan and obtaining suggestions for improvements through discussion.

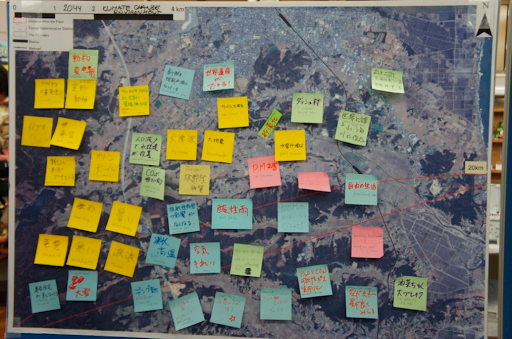

One of the maps of the brainstorming session. Source: Zhang, H., Mao, Z., & Zhang, W. (2015).

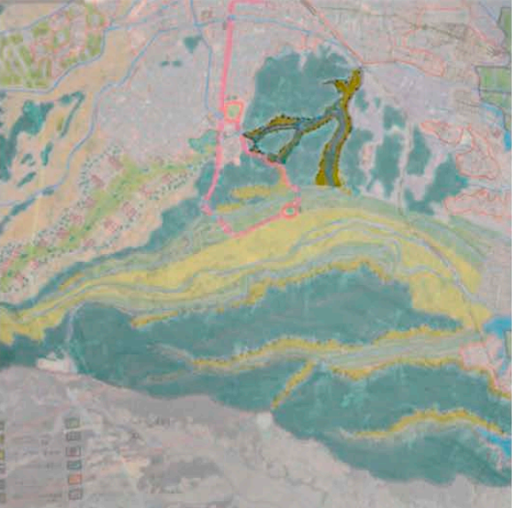

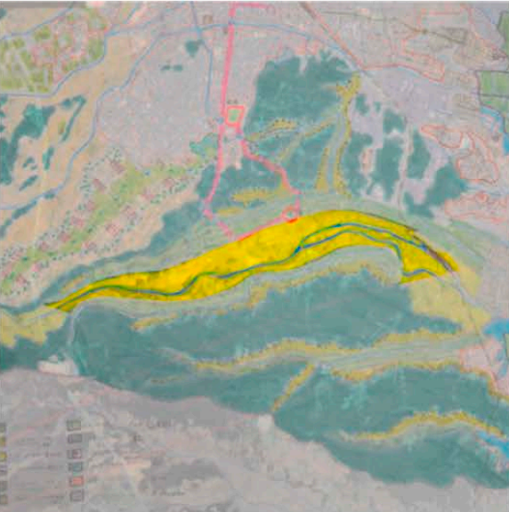

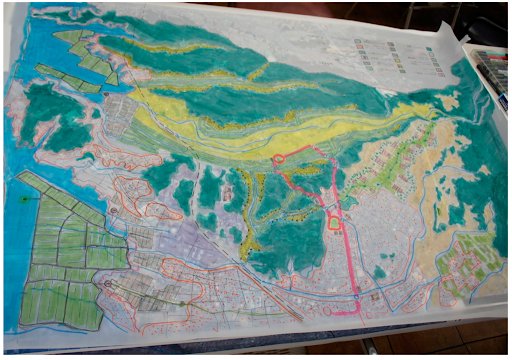

In the design process, the key areas that were covered by the plans were labelled on a map with GIS technology. GIS technology was used to draw the map of the study area. The map provided the information of geographical features, the current status of land use and the evacuation zone established by the government. The participants then covered a poster-sized map with a transparent sheet, and the design plans were drawn by hand on the sheet. The participants presented a four-phase recovery plan for nuclear-contaminated farmlands.

The design charrette was a new model for post-disaster recovery assistance in Minamisoma. The charrette’s contributions included the following aspects:

Establishing an integrated perspective for the decision-making process.

Promoting communication and collaboration.

Inspiring new reconstruction ideas.

Regenerating post-disaster resilience. The design charrette encouraged residents to demonstrate confidence and courage in post-disaster reconstruction.

The clay modelling session. Source: Zhang, H., Mao, Z., & Zhang, W. (2015).

Lessons Learnt

The Minamisoma charrette was based on GIS technology and was run with the participation of multiple stakeholders in an intercultural, intergenerational and interdisciplinary collaboration. Among lessons learnt

The charrette helped the residents consider post-disaster reconstruction in its totality.

The involvement of stakeholders in the entire decision-making process promoted communication and collaboration between the various parties.

Residents contributed reconstruction alternatives to the decision makers.

The design charrette recreated a post-disaster resilience in the community.

Footnotes

[1] The experts were from Keio University in Japan, Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, and VHL University of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands. All of the land-use and landscape-design experts were from non-Japanese-speaking countries. Local residents were recruited by the local NGO and participated voluntarily.

References

Hui Zhang, Zijun Mao and Wei Zhang 2015. ‘Design Charrette as Methodology for Post-Disaster Participatory Reconstruction: Observations from a Case Study in Fukushima, Japan’. Sustainability, 7, 6593–6609; doi:10.3390/su7066593