Case Study extracted from Salat, Serge. 2021. Integrated Guidelines for Sustainable Neighbourhood Design. Urban Morphology and Complex Systems Institute 2021. © UMCSII.

Positive feedback loop of land value capture in king’s cross, london, uk

Land value capture (LVC) mobilises for the community the land value increases generated by public investments in infrastructure or administrative changes in land use norms and regulations. This reading provides lessons for practitioners on how to create positive feedback loops of development with land value capture (LVC). It explains the step-by-step strategies that can be used and illustrates them with a case study in King’s Cross, London, UK.

Key partners and actors

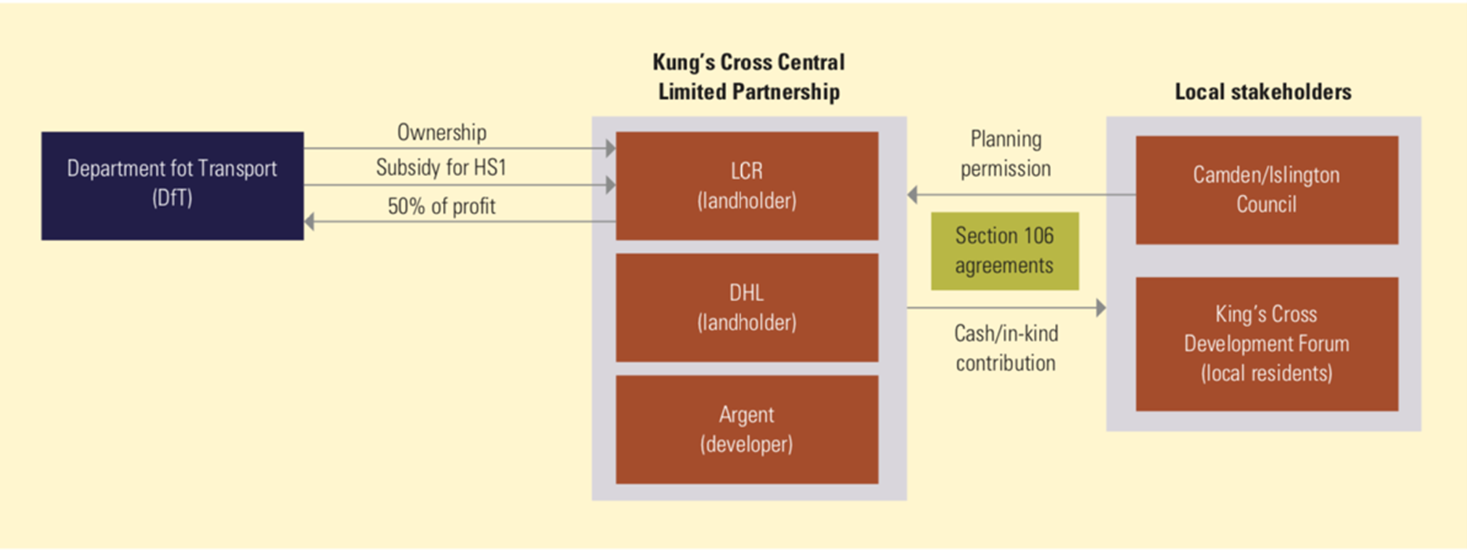

The King’s Cross Central Limited Partnership (KCCLP) is developing the mixed-use scheme. KCCLP is the collective name for the single landowner that comprises three groups: U.K. property developer Argent (owning 50% via Argent King’s Cross Limited Partnership); the U.K. state-owned London and Continental Railways Limited (LCR), holding a 36.5% interest; and DHL Supply Chain (formerly Exel), with a 13.5% stake.

Argent’s subsidiary, Argent King’s Cross Limited Partnership, is developer and asset manager at King’s Cross. It is backed by Argent LLP and Hermes Real Estate on behalf of the BT Pension Scheme. The development philosophy is holistic, with all the landowners working together within one overarching, shared vision. The stakeholders in the project have remained the same since 2001. The three principal contractors are BAM, Carillion, and Kier.

Creating a positive feedback loop of neighbourhood development in four steps

Infrastructure investment leading to enhancements in accessibility and urban quality fosters raises in land value. Capturing them starts a positive feedback loop. The unlocking of underused assets (land or structures) potential value because of a public sector intervention (rezoning or provision of transit infrastructure) stimulates demand from the private sector. Subsequent investment and development from the private sector ensure the realisation of asset value increase. The constant reinvestment of the value created and captured creates progressively more and more value.

Positive Feedback Loop of Value Capture Finance. Source: Huxley 2009.

How can the positive feedback loop be triggered and fostered? Four steps are necessary.

Value Creation. Value creation strategies involve improving connectivity, place making with high quality public realm, and market stimulation, with each supporting the others. Public investment in parks, mass transit, and infrastructure will help make these places the most liveable areas of their cities.

Value Realisation. Private sector investment, comprehensive master planning, and area promotion increase potential asset values.

Value Capture. Higher asset values are captured for private profit and the public good. Private value capture is primarily via the rent or sale of new or enhanced housing, retail, or office units. The public sector can use a range of mechanisms to capture enhanced asset values realised by private actors.

Local Value Recycling. The captured value can be recycled, or reinvested in the same development through the public- or private sector-led reinvestment. In the case of the public sector – led reinvestment, increased public revenues captured from the private sector through higher local taxation, fees, and levies pay for additional government interventions within the same development area. This reinforces asset values and has positive social-economic impacts.

Case study: Value capture finance positive feedback loops in King’s Cross, London, UK

King’s Cross area redevelopment features important aspects connected to value creation, realisation, capture, and recycling. The case study is therefore structured around these four crucial aspects of LVC and how they financed positive feedback loops.

Value Creation

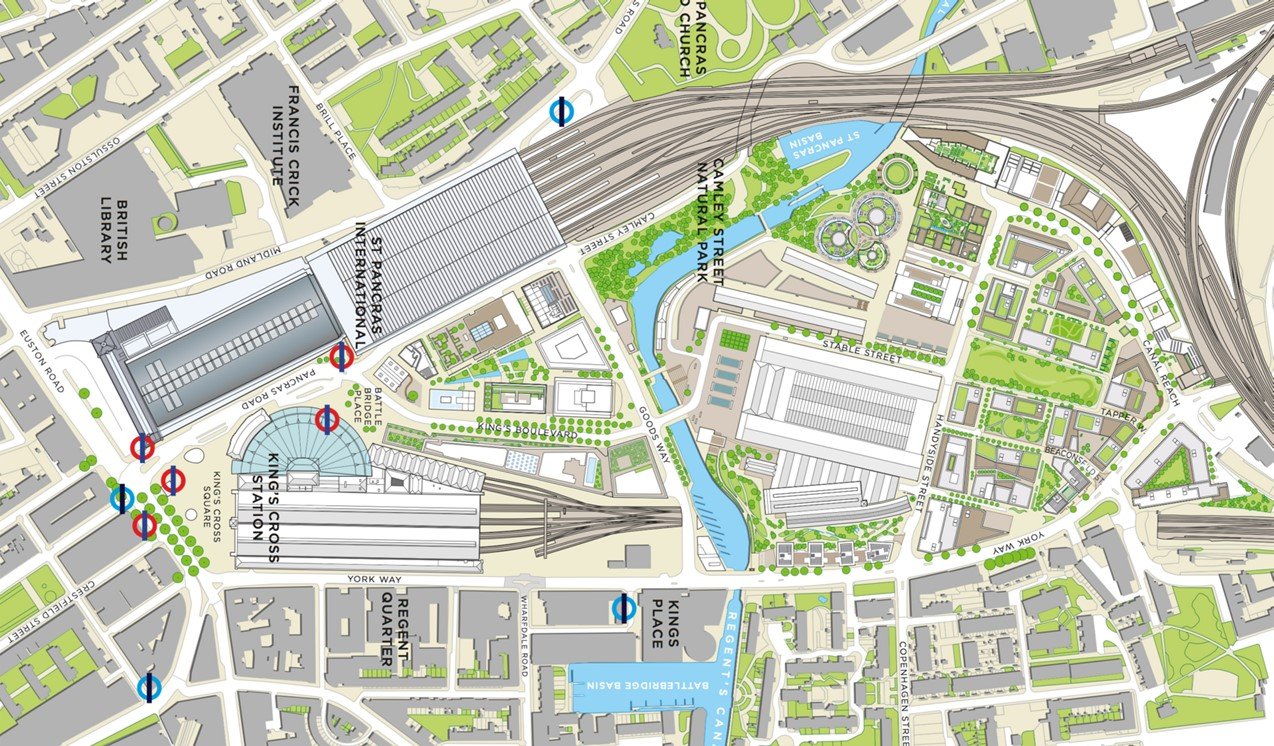

King’s Cross is a Central London mixed-use urban regeneration project centred on a major multimodal transportation hub. A highly tailored scheme resulted from two master planning teams and four independent design review panels. In King’s Cross Central and along Crossrail in London, public investment in transport infrastructure and high-quality urban landscaping created value peaks. Several public interventions made these places desirable.

Land use transformations and place making using planning and regulatory tools took the form of rezoning at higher values, with mixed use and with margins of flexibility. This allowed them to capture value between base and maximum and to adapt to market changes. Rezoning at higher FARs levels created higher market values in well-connected areas, centrally located, with a high demand at city scale.

King’s Cross Central site before regeneration. Source: © King’s Cross Central Limited Partnership

The welcoming King’s Cross Square after regeneration. Photo: © Françoise Labbé

Moreover, in King’s Cross Central, 20 heritage buildings were retained and refurbished as shops and restaurants. Their colour and character display the unique nature of the development. The high density, mix use, infill redevelopment with an average FAR of 4.6 at block scale combines heritage and new buildings. High density has been reached through a great diversity of 50 building structures at human scale, defining public pace with legibility and vibrant edges. The developers decided to combine high density with a high-quality urban environment and heritage buildings, creating a unique blend of history, culture, and contemporary.

The development added twenty new connective streets. This diagram illustrates the aim to create a network of safe pedestrian routes and other linkages, to help join places together and integrate the development with existing neighbourhoods and communities in Camden and Islington. Source: EDAW 2004.

Enhanced infrastructure provision took the form of future linkage uniting King’s Cross and Euston Square into a single station, with HS1 and HS 2. This will create the biggest interchange across several geographical scales in the UK connecting Europe, UK, and London with High-Speed Rail, National Rail, 6 subway lines, and 17 bus routes. Up to now, investment in local transport infrastructure totals £2.5 billion (3.6 US$ billion).

Comprehensive master planning. In King’s Cross Central, developers designed innovative master plans, with quality public space and local connectivity. High levels of public participation supported the planning effort.

The high-quality public spaces programme of King’s Cross station. Source: Argent 2014.

Enhanced urban value and image. High-quality public space and iconic architecture is a crucial strategy in King’s Cross Central.

Environmental and social enhancement. King’s Cross Central project comprised an important component of combining physical regeneration (e.g. developing sites, refurbishing buildings) with community revitalization (e.g. providing skills).

Population and jobs’ growth. In King’s Cross, a huge increase in human density is planned for jobs and for residential, creating very dense mixed-use communities. By 2020, up to 45,000 people will be living, studying, working in King’s Cross, which represents a peak of human density (residential + jobs) of nearly 1,700 people per ha on the 27 ha of the site.

Value Realisation

Public and private sector involvement and investment increased tangibly asset values in many ways.

Public sector direct investment. Since the land agreement in 2009 between Camden County and the developer, King’s Cross Central has been funded through a combination of equity, senior debt, and recycled receipts. Cash flow management has enabled the partnership’s equity to be used across a variety of projects to create the demand and interest from potential buyers. The partnership has made a £250 million investment in public realm infrastructure at King’s Cross Central since 2009. This has unlocked the 557,000 m2 of development on the project. The partnership’s equity funding went in priority towards the creation of the public realm: new roads (including King’s Boulevard), new public spaces (including Granary Square), a new bridge across Regent’s Canal, canal-side improvements, and the Energy Centre and its associated district heating and distribution networks. Besides, KCCLP entered a £100 million construction contract with the University of the Arts for its campus (ULI 2014).

Private sector investment. Google, for example, has spent about £650 million to buy and develop a 1 ha site on a 999-year lease from King’s Cross Central Limited Partnership (KCCLP), the partnership developing the site. The finished development [93,000 m2] will be worth up to £1 billion. Several thousand staff will occupy the low-rise structure when it is complete. GOOGLE UK headquarters will be its largest office outside its Googleplex corporate headquarters in California. The building includes 4,650 m2 of ground-floor retail. Google presence is expected to draw other technology companies to King’s Cross – especially small start-ups – and help bump up rents

Area promotion through enhanced destination branding and marketing. King’s Cross Central redevelopment transformed a derelict industrial rail yards area into a beacon for creative professionals. The area is becoming the home of Google and other fast-growing technology and digital media firms.

The new Google headquarters in King’s Cross Central. Parts of the building will overlook canals in the King’s Cross area. Image: Google.

Value Capture

Increased asset values are captured both for the public good and private profit. We provide below a general list of value capture finance instruments, derived from Huxley 2009.

-

Land held in private or public ownership is provided to the public promoter for public use.

-

Local general targeted taxation and local real estate tax increases where revenues are reinvested into the same area in which they were collected.

-

Planning approval fees, development levies and infrastructure tariffs.

-

Item descriptionSecuring loans against the increased or future value of the land.

-

Private actors concur to give priority to the local community for access to new facilities, public space or to manage basic public services.

-

For instance, schools, community centres, affordable housing, transport links and utility provision and upgrade, were part of the agreement between the local government and private developer for King’s Cross Central.

-

Stakeholders in the land value capture scheme and Section 106 agreements. Source: Suzuki et al. 2015.

The Section 106 Agreement around King’s Cross includes cash and in-kind contributions to the provision of local infrastructure, public space and community services by the joint developer for the Camden Council. One key LVC technique adopted by local governments in England and Wales is their use of Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act of 1990. This section provides a means for local authorities to negotiate agreements or planning obligations with a landowner or developer with the granting of planning permission to offset the impact of development. In the case of King’s Cross, Section 106 agreements have been crucial in incorporating desirable planning principles into public-private funding and property development. The use of Section 106 agreements around King’s Cross underlines the importance of balancing interregional business marketability and local community liveability with PPP-based infrastructure funding and property development (Suzuki et al 2015).

The agreement for King’s Cross Central redevelopment contained ‘floor space maxima’ to guarantee diverse site use. These allocation figures allow for flexibility, as redevelopment is likely to take 10–15 years to complete. The permission allowed 20 percent flexibility to vary the mix of uses within the total floor space. Thus, floor space of one use could, to a limited extent, be traded against another, depending on market conditions. This flexibility allows the plan to be adapted to market conditions along the course of development, with adjustments to the land uses made according to market demand.

The public sector uses a range of mechanisms to capture enhanced asset values realised by private actors. The Section 106 Agreement around King’s Cross includes cash and in-kind contributions to the provision of local infrastructure, public space and community services by the joint developer for the Camden Council. These include £2.1 million to create 24,000–27,000 local jobs through a Construction Training Centre and Skills and Recruitment Centre; 1,900 homes, more than 40 percent of which will be affordable housing; cash and in-kind contributions for the community, sports, and leisure facilities; new green public spaces, plus new landscaped squares and well-designed and accessible streets, accounting for about 40 percent of the entire site; a new visitor centre, education facilities, and a bridge across the canal to link streets; and cash contributions to improve adjacent streets, transit stops, and bus services.

Local Value Recycling

The captured value (in monetary form or ‘credit’ to leverage in-kind contributions from the private sector) can be recycled or reinvested in the same scheme for the public good in two main ways.

-

Heightened public revenues captured from the private sector through enhanced local taxation, fees and levies pay for additional government interventions within the same development zone. This reinforces asset values and social-economic impacts.

-

The public actor offers private partners the opportunity to deliver community-oriented infrastructure directly. This increases further asset values.

Lessons Learnt

Being able to capture land value and finance positive feedback loops is a crucial aspect of sustainable neighbourhoods’ development. King’s cross case study, displaying a mixture of tax-based and development-based value capture finance instruments, is an outstanding example of the strategies necessary to successfully pursue LVC and positive feedback loops. To properly trigger and foster positive feedback loops, some steps and strategies must be tailored according to contextual features. The case study here displays the crucial stages to create, realise, capture and recycle land value, thus rendering investments for urban development financially sustainable while simultaneously revitalising underutilised assets within cities.

References

Huxley, J. 2009. Value Capture Finance. Making Urban Development Pay Its Way. London:

Urban Land Institute. http://uli.org/wp-content/uploads/ULI-Documents/Value-Capture-Finance-Report.pdf

Salat, S., Ollivier, G. P. 2017. Transforming the urban space through transit-oriented development: the 3V approach (English). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/647351490648306084/Transforming-the-urban-space-through-transit-oriented-development-the-3V-approach

Smolka, M. O. 2013. Implementing Value Capture in Latin America, Policy Focus Report. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Suzuki, H., Murakami, J., Hong, Y.-H., and Tamayose, B. 2015. Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries. Urban Development Series. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0149-5. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

ULI Case Studies, King’s Cross, July 2014.